The following article was originally published in the introductory leaflet accompanying the CD-ROM guide Birds of Sri Lanka: Vocalization and Image Guide. Vol.1 (2008) by D. Warakagoda and U. Hettige. It is featured here with some changes as an aid to understanding the main subject dealt with in this website and the audio publications on this subject by the Library. Now included below are relevant sound clips of birds and their images. Bird sound recordings by Deepal Warakagoda, and photos by Sudheera Bandara (SB) and Gehan Rajeev (GR).

by Deepal Warakagoda

Among birds vocal sound is one of the best methods of communication to aid them to survive successfully in their environment. Its results are most evident in escaping from danger and success in breeding, which directly govern the survival of a species.

Some birds which do not produce vocal sounds (e.g. Storks, in the family Ciconiidae) produce non-vocal sounds with the bill. Some bird species produce both vocal and non-vocal sounds.

Bird vocalizations can be recognized as two types, calls and songs, by examining the structure of a sound and the benefit related to it.

A call is a note or a phrase of very few notes for communication between a pair or among a family or flock, usually uttered to be in contact, indicate the approach of danger, the availability of food, or hunger by nestlings.

A song is a phrase of very few to many notes which is repeated at regular intervals. It is uttered mostly by the male, and is important in breeding behaviour, establishing and defending territories, and attracting mates. Females join males, sometimes in singing to defend territory, and regularly in duetting: see below. Often different types of behaviour or postures are seen with different types of song in the same species.

Songs of the true songbirds, who are all Passerines*, are pleasant and “musical”, and usually complex and varied–examples are larks, thrushes, robins, and some flycatchers among Sri Lankan birds. The songs of most Sri Lankan Passerines other than true songbirds are varied though not so complex–examples are ioras, leafebirds, bulbuls, warblers, drongos and orioles. Many Passerines include in their songs mimicry of calls or songs (in part or whole) of other birds, or this is uttered separately–examples are the White-bellied drongo and Jerdon’s Leafbird, the former mimicking the domestic cat and Shikra, the latter the Shikra and other birds. Most Non-Passerine† birds do not have complex or varied songs, but some do have pleasant and musical songs–examples are the cuckoos.

* In Sri Lanka, Families of birds from Pittidae (Indian Pitta) to Emberizidae (buntings).

† In Sri Lanka, Families of birds from Phasianidae (junglefowl, peafowl, etc.) to Picidae (woodpeckers).

Distinct types of calls are:

Contact calls, to maintain contact between a pair, especially when they are some distance apart, and within members of a family or flock, e.g. made by the Yellow-billed Babbler.

Flight calls, made in flight to maintain contact within flocks of Whistling Ducks and shorebirds, and among individuals of some species while taking wing, e.g. wagtails, pipits, mynas.

Aggressive calls, uttered at other birds of the same species, or sometimes at other bird species or animals, to threaten them, e.g. Oriental Magpie Robin, Black-hooded Oriole, Blyth’s Reed Warbler.

Scolding and alarm calls, to announce danger in the vicinity, a typical alarm call often being a rapidly uttered single note announcing the approach of danger with high risk, e.g. Red-vented Bulbul.

copulation calls, uttered while copulating, only by a few species, e.g. the Shikra.

Distinct types of songs are:

Advertising songs, to announce the ownership of a territory or to attract a mate.

Territorial songs, to announce the ownership of a territory – with the same song/s being used for both purposes above by most species.

Courtship songs, to attract a female after approaching her or to entice her to copulate.

Aggressive songs, to threaten an intruder, usually a male, of the same species approaching a territory (see no. 11) – again, most species using the same song/s for both the above purposes.

Duetting songs or duets, territorial songs in which both birds of a pair sing, in the same session, the same phrase or different phrases; in some duets this is so close in succession that this is heard like a continuous song sung by one bird–e.g. by the Sri Lanka Spurfowl, Brown Fish Owl, and Sri Lanka Scimitar Babbler.

Subsongs, males of many Passerine birds sing long phrases of softly uttered notes during the non-breeding season. This is usually done while sitting quietly on a less exposed low branch of a tree. This kind of singing seems to provide practice for the adult males before they sing their loud, full songs in the breeding season. Young males babble phrases somewhat reminiscent of full songs of their adults in their practice of singing songs. E.g. Oriental Magpie Robin and Blyth’s Reed Warbler.

In many species the song of the male and the female differ only or mostly by the pitch, with the same or very similar phrase –e.g. Greater Coucal, Owls (Collared Scops Owl, Brown Hawk Owl and Brown Fish Owls.

In all Non-Passerine, and some Passerine, species, it can be difficult to make out whether certain vocalizations are calls or songs.

Non-vocal sounds related to territorial and breeding behaviour are known in bioacoustics as mechanical sounds–examples in Sri Lanka are bill clattering in storks, wing clapping by the Junglefowl, pigeons and doves, and the drumming of woodpeckers by very rapid striking of the bill on a resonant tree.

Oriental Skylark – Photo by SB Oriental Skylark – song

Oriental Skylark – Photo by SB Oriental Skylark – song Spot-winged Thrush – Photo by SB Spot-winged Thrush – songs

Spot-winged Thrush – Photo by SB Spot-winged Thrush – songs Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – songs

Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – songs Common Iroa – Robin Photo by GR Common Iora – songs

Common Iroa – Robin Photo by GR Common Iora – songs Jerdon’s Leafbird – Photo by GR Jerdon’s Leafbird – a song

Jerdon’s Leafbird – Photo by GR Jerdon’s Leafbird – a song Black Bulbul – Photo by SB Black Bulbul – a song

Black Bulbul – Photo by SB Black Bulbul – a song White-bellied Drongo – Photo by GR White-bellied Drongo – a song

White-bellied Drongo – Photo by GR White-bellied Drongo – a song Black-hooded Oriole – Photo by GR Black-hooded Oriole – songs

Black-hooded Oriole – Photo by GR Black-hooded Oriole – songs White-bellied Drongo – Photo by GR White-bellied Drongo – mimics Shikra

White-bellied Drongo – Photo by GR White-bellied Drongo – mimics Shikra Indian Cuckoo – Photo by GR Indian Cuckoo – song

Indian Cuckoo – Photo by GR Indian Cuckoo – song Banded Bay Cuckoo – Photo by … Banded Bay Cuckoo – song

Banded Bay Cuckoo – Photo by … Banded Bay Cuckoo – song Drongo Cuckoo – Photo by GR Drongo Cuckoo – song

Drongo Cuckoo – Photo by GR Drongo Cuckoo – song Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – calls

Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – calls Yellow-billed Babbler – Photo by GR Yellow-billed Babbler – calls

Yellow-billed Babbler – Photo by GR Yellow-billed Babbler – calls Yellow-billed Babbler – Photo by GR Yellow-billed Babbler – soft calls

Yellow-billed Babbler – Photo by GR Yellow-billed Babbler – soft calls Yellow Wagtail – Photo by GR Yellow Wagtail – flight call

Yellow Wagtail – Photo by GR Yellow Wagtail – flight call Paddyfiled Pipit.Photo by SBPaddyfiled Pipit – flight call

Paddyfiled Pipit.Photo by SBPaddyfiled Pipit – flight call Common Myna – Photo by GR Common Myna – flight cal

Common Myna – Photo by GR Common Myna – flight cal Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – aggressive call

Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – aggressive call Black-hooded Oriole – Photo by GR Black-hooded Oriole – aggressive call

Black-hooded Oriole – Photo by GR Black-hooded Oriole – aggressive call Blyth’s Reed Warbler- Photo by GR Blyth’s Reed Warbler – aggressive call

Blyth’s Reed Warbler- Photo by GR Blyth’s Reed Warbler – aggressive call Red-vented Bulbul- Photo by GR Red-vented Bulbul – alarm call

Red-vented Bulbul- Photo by GR Red-vented Bulbul – alarm call Red-vented Bulbul- Photo by GR Red-vented Bulbul – scalding calls

Red-vented Bulbul- Photo by GR Red-vented Bulbul – scalding calls Yellow-billed Babbler – Photo by GR Yellow-billed Babbler – alarm calls

Yellow-billed Babbler – Photo by GR Yellow-billed Babbler – alarm calls Shikra- Photo by GR Shikra – the call uttered when pair copulating

Shikra- Photo by GR Shikra – the call uttered when pair copulating Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – advertising songs

Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – advertising songs Brown-capped Babbler- Photo by GR Brown-capped Babbler – advertising song

Brown-capped Babbler- Photo by GR Brown-capped Babbler – advertising song Spotted Dove – Photo by SB Spotted Dove – advertising song

Spotted Dove – Photo by SB Spotted Dove – advertising song Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – courtship song

Oriental Magpie Robin – Photo by GR Oriental Magpie Robin – courtship song Yellow-eyed Babbler- Photo by SB Yellow-eyed Babbler – aggressive songs

Yellow-eyed Babbler- Photo by SB Yellow-eyed Babbler – aggressive songs Spotted Dove – Photo by SB Spotted Dove – courtship & aggressive song

Spotted Dove – Photo by SB Spotted Dove – courtship & aggressive song Brown-capped Babbler- Photo by GR Brown-capped Babbler – courtship & aggressive song

Brown-capped Babbler- Photo by GR Brown-capped Babbler – courtship & aggressive song Red-vented Bulbul- Photo by GR Red-vented Bulbul – courtship song, sung softly

Red-vented Bulbul- Photo by GR Red-vented Bulbul – courtship song, sung softly Sri Lanka Spurfowl- Photo by SB Sri Lanka Spurfowl – duet of a pair

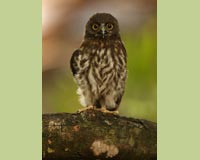

Sri Lanka Spurfowl- Photo by SB Sri Lanka Spurfowl – duet of a pair Brown Fish Owl- Photo by SB Brown Fish Owl – the duet of a pair.

Brown Fish Owl- Photo by SB Brown Fish Owl – the duet of a pair. Greater Coucal – Photo by GR Greater Coucal – a pair calling at different pitch.

Greater Coucal – Photo by GR Greater Coucal – a pair calling at different pitch. Brown Hawk Owl – Photo by SB Brown Hawk Owl – single bird calling first and then it is joined by its mate on different pitch

Brown Hawk Owl – Photo by SB Brown Hawk Owl – single bird calling first and then it is joined by its mate on different pitch Brown Fish Owl – Photo by GR Brown Fish Owl – the duet of a pair, the two birds on different pitch.

Brown Fish Owl – Photo by GR Brown Fish Owl – the duet of a pair, the two birds on different pitch. Collared Scops Owl – Photo by GR Collared Scops Owl – the duet of a pair, the two birds on different pitch.

Collared Scops Owl – Photo by GR Collared Scops Owl – the duet of a pair, the two birds on different pitch. Black-rumped Flameback – Photo by GR Black-rumped Flameback – drumming

Black-rumped Flameback – Photo by GR Black-rumped Flameback – drumming Crimson-backed Flameback- Photo by GR Crimson-backed Flameback – drumming

Crimson-backed Flameback- Photo by GR Crimson-backed Flameback – drumming